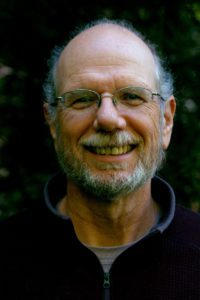

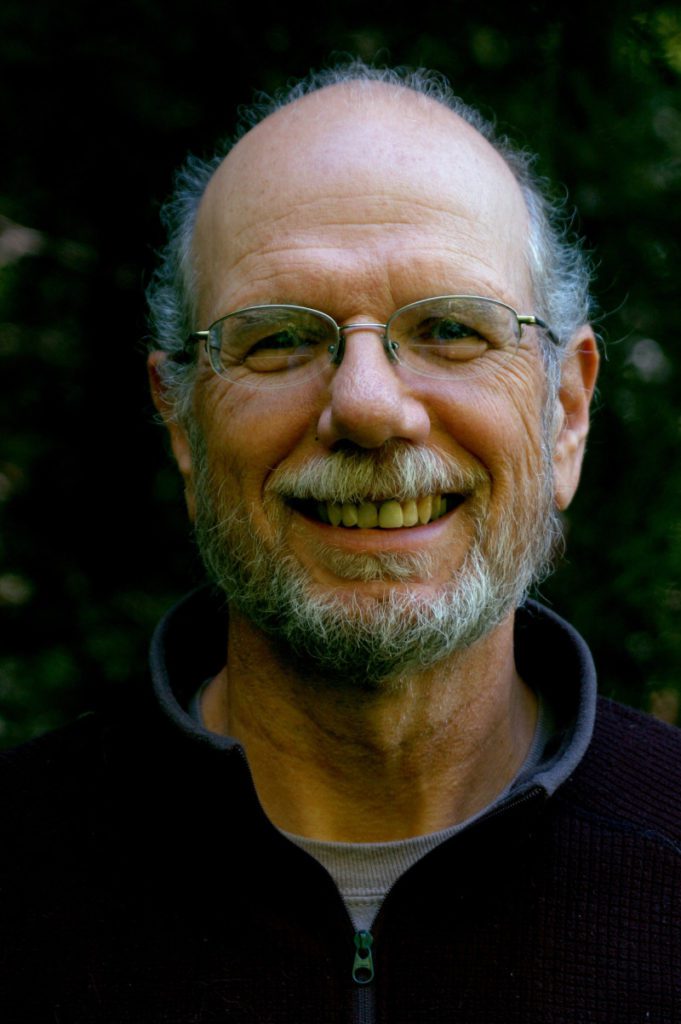

By James M. Jackson

By James M. Jackson

Answer me this: It’s summer. I point to any sugar maple in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan forest my protagonist Seamus McCree calls home and ask, what color are its leaves?

We all know the answer: green.

Yet, what I cannot know is if the “green” you see is the same “green” I see. We were both taught by parents, teachers, books that sugar maple leaves in the summer are green. The grass on our lawns is also green (if we watered and fertilized, otherwise it might be brown). We can agree on the physics: light reflecting from a particular leaf has the same wavelength regardless of the viewer. Differences arise when those light waves reach our eyes, and our brains interpret them.

My son’s eyes have a higher proportion of green cones than normal, which, doctors tell me, means he sees green more brightly than I. That may explain why his favorite clothing as a toddler were his green Oshkosh B’gosh overalls. (Or maybe they fit better than anything else.) But it doesn’t tell me what he sees, nor can he know what I see. And while we have a physical explanation of why my son and I should see differently, the fact is, I don’t know what you see when you look at a leaf either.

It’s not simply our physical differences that cause us to experience the world differently. We process and evaluate information based on our previous experiences. Writing from a character’s point of view requires me to put on their blinders, employ their filters, experience and describe the world as the character would. Seamus is a numbers guy, and he asks questions like: “On a scale of one to ten . . .” He thinks more often than he feels. He enjoys being outdoors, and he particularly enjoys birdwatching. Even if he’s not actively birdwatching, he notices their colors, their mannerisms, their songs, and when they are quiet. His brain’s overload filter lets in all things bird.

Others might block out the birds and notice instead faint tracks in the dirt, a broken twig, crushed grass from the passing of an animal. Still others might ignore nature altogether, worried only about mosquitoes and ticks and making it back home in time for their daily glass of wine without wolves, bears or cougars attacking them.

Different perspectives can lead to conflict, even death. Sometimes they provide a humorous character insight. That happens in the “eagle subplot” in Granite Oath, the seventh Seamus McCree novel. The subplot kicks off with Megan, Seamus’s eight-year-old granddaughter announcing, “Grampa Seamus. We’re training an eagle.”

Later, after Seamus witnesses Megan and her friend Valeria calling in a family of eagles to grab fish they have left, Megan explains how it started:

“We accidentally left a fish on the dock and saw the eagle grab it.” She slid me a look. “Pier. You told me. Piers stay in the water, docks come out for winter. We did a science experiment and left one on purpose. The fish have to be keepers. They won’t come for the little ones.”

Seamus thinks to himself that the kids aren’t training an eagle, the eagle is training the kids.

Same event, different perspectives. I’m sure you’ve experienced something similar, and I’d loved to hear about it in the comments.

* * *

Mini-bio:

Mini-bio:

James M. Jackson authors the Seamus McCree series. Full of mystery and suspense, these domestic thrillers explore financial crimes, family relationships, and what happens when they mix. August 2022 saw publication of the 7th novel in the series, Granite Oath. (Click here for information and purchase links.)

Jim splits his time between the wilds of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the city life in Madison, WI. You can find more information about Jim and his books at https://jamesmjackson.com or contact him via email.

Thanks for having me today, Debra. I’ll stop by later and respond to any comments.

My pleasure. Loved the new book (Granite Oath).

James M. Jackson, I thought I was the only one pestering my parents when I was young with questions about whether everyone saw the colors the same. My father was colorblind and when asked about colors of clothing he called everything brown or grey, so I realized we did not all see things the same. Of course, my early questioning did not include the different perspectives we might have or how others might see the world. I’m still working on that one. The older I get, the more I realize what differences we all have in how we see things.

Carol,

Thanks for stopping by. I never thought about a color blind person trying to explain colors to a child. What an interesting perspective you raise. Think Jim’s blog hit it right on so many points.

Carol, I echo Debra’s comment regarding how it must be to try to explain colors when one is color-challenged. I did consider for a short-story (unwritten) how someone who was not hearing impaired might mispronounce words because she heard them from parents who were hearing impaired.

So much in life yet to learn, and I am running out of time.

Leave it to Jim Jackson to give us such a thoughtful essay! Thanks for this. It makes me think of all the other things we can’t know about our fellow humans.

You’re welcome, Kaye. I agree that we make many assumptions about other folks — some of them are even correct. 🙂

You are so right, Kaye. Jim gave us much food for thought.

Thanks so much for this post. I’ve thought about the color issue for years. My first-grade friend Marlu colored her tree trunks brown; I thought she was crazy and colored mine black. Two years later, with corrective lenses for myopia, I saw brown trunks. Oil painting lessons turned them from brown to a variety of colors. Interesting. But recently, when my husband told me to disconnect the yellow cable and I saw only a beige cable, I began to worry. I was relieved when he later showed me I’d been looking in the wrong place.

Kathy,

Loved your comment. It was a perfect example of what Jim was saying, but the punch line about the cable made me roar.

Kathy, your “I thought she was crazy” is so spot on, because of course it’s not us. It reminds me of the quote from Robert Owen: All the world is queer (strange) save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer. And then we discover it is us and we sometimes become over-reactive the other way — to humorous result in your story. Thanks.